Riyad Wadia

(1967-2003)

Wish you were here …

Do you think you can tell, heaven from hell, blue skies from pain …

“There are some moments in one’s artistic career where the mind, the soul, and the medium all mesh together to create a work that comes from the heart. For me, the making of BOMgAY was that moment,” 1 wrote Riyad Wadia about his 12-minute film on gay life in South Bombay. Some said it was elitist and he graciously accepted the charge, explaining that he’d never meant to make another kind of film in the first place. He preferred to stick to what he knew.

“There are some moments in one’s artistic career where the mind, the soul, and the medium all mesh together to create a work that comes from the heart. For me, the making of BOMgAY was that moment,” 1 wrote Riyad Wadia about his 12-minute film on gay life in South Bombay. Some said it was elitist and he graciously accepted the charge, explaining that he’d never meant to make another kind of film in the first place. He preferred to stick to what he knew.

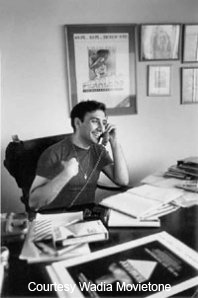

Riyad Wadia is the perfect person to package in a discourse. He was goodlooking, talented and made gay films. He was also the scion of one of Bombay’s founding families and died young. While all of this is true, it encases him in clichés, the biggest, most contentious and most problematic one of all being gender. Riyad Wadia’s work engaged with gender frontally. He made no bones about the fact that he was gay, that his films were about gayness and alternative sexualities. And he presented these on their own terms confidently, rejecting polarities and instituting integrity.

This integrative approach was at the basis of how he approached filmmaking in general. For him “the mind, the soul and the medium all mesh(ed) together.” You can ask whether Aida Banaji, his transsexual subject in A Mermaid Called Aida,2 – is real or fantastical? But his view is – what’s the difference? Why not make the real fantastical and the fantastical real? Like the spoofed interviews in the film, for example. Why not merge dream and reality, like in the library scene in BOMgAY? And lastly, why not merge work and play.. and play with our sexuality? But this is where it sticks ….

This integrative approach was at the basis of how he approached filmmaking in general. For him “the mind, the soul and the medium all mesh(ed) together.” You can ask whether Aida Banaji, his transsexual subject in A Mermaid Called Aida,2 – is real or fantastical? But his view is – what’s the difference? Why not make the real fantastical and the fantastical real? Like the spoofed interviews in the film, for example. Why not merge dream and reality, like in the library scene in BOMgAY? And lastly, why not merge work and play.. and play with our sexuality? But this is where it sticks ….

Riyad Wadia began his career with Fearless – The Hunterwali Story,3 a documentary on Nadia née Mary Evans who was his great aunt. She played the character of Hunterwali (among several others) in the films of Wadia Movietone founded in 1933 by JBH Wadia and Homi Wadia who were his grandfather and grand uncle. Fearless was a huge success. It traveled to festivals across the world and revived Nadia in a fashionable new avatar – India’s blonde and blue-eyed stunt queen – which she undoubtedly was, except that she was more than that.

JBH, as he was known, said in an interview included in Fearless that Hunterwali was a counterpoint to the teary ‘Hindu’ heroines of the time. While the Achhut Kanyas of the time were dealing with the genteel feminism budding inside of them, Nadia was the Bambaiwali4, lifting men and throwing them down the stairs. She was a gender-bender.But the thread was lost. The new Indian nation was building a ‘modern’ culture which liked to categorize, label and control. Nadia was too much of an oddity and was transmuted into gender-defined stereotypes such as the action hero or the angry young man5. Strange to think of Deewar’s Vijay tracing part of his ancestry to Nadia but this is how it was. Her co-actors, became some of Bollywood’s leading stunt men and fight directors.

Nadia differed from the action hero and angry young man in one crucial aspect. She was funny, irreverent and in many ways a caricature of herself. She was serious about defeating evil, but did it tongue-in-cheek, with humour and without pomposity. We’re getting back into that mode now. Drama is getting to be passé and irreverence is in – matched by genres which are irreverent too – you have spoofs ( the Saigal parody in Delhi Belly and the familial interviews in A Mermaid Called Aida), vignettes (BOMgAY), micro-narratives (Onir’s I Am), and the family-video-turned-superb coming-out film, Summer in my Veins, by Nish Saran who, at the age of 23 in 1999, filmed himself revealing his homosexuality to his mother.

All these films show up the inadequacy of stereotypical identity. In the 4 micronarratives in Onir’s I Am, the gay story is one among three others, linking gayness to other contemporary issues – Megha is divided between her Kashmiri and Hindu selves, Afia’s child’s father will be an anonymous sperm donor, the notion of the nurturing parent is challenged by the story of Abhimanyu and that of gender as strictly male or female by Omar. Onir’s Nikhil in My Brother Nikhil, too, is no effeminate gay. He is tough and macho, desired by both men and women. And Aida is a transsexual with a successful career in finance.

All these films show up the inadequacy of stereotypical identity. In the 4 micronarratives in Onir’s I Am, the gay story is one among three others, linking gayness to other contemporary issues – Megha is divided between her Kashmiri and Hindu selves, Afia’s child’s father will be an anonymous sperm donor, the notion of the nurturing parent is challenged by the story of Abhimanyu and that of gender as strictly male or female by Omar. Onir’s Nikhil in My Brother Nikhil, too, is no effeminate gay. He is tough and macho, desired by both men and women. And Aida is a transsexual with a successful career in finance.

Other oppositions are collapsing too – ‘alternative’, for example, is getting to be ‘mainstream’ and ‘small’ is replacing ‘big’. Raavan starring Aishwarya Rai and Abhishek Bachchan was a flop but Band Baaja Baaraat with a couple of unknowns in the lead was a hit. Another telling example is Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron, an absurd, black comedy made on a 7-lakh budget which flopped in its own time (1983) but has now been revived.

‘Small’ is replacing ‘big’ in technology too. Equipment is affordable, user-friendly, less cumbersome. BOMgAY was made in 18 days on a budget of 2 lakhs. It was shot on Beta and edited by on an Avid system.6 Summer in my Veins7 by Nish Saran, was shot on a videocam. Cheaper technology is facilitating newer genres and fresher perspectives. This is borne out by a lot of the new crop of films made by the new generation of film makers – Dev D was made on a budget of 7 crores as opposed to 50 crores spent by Sanjay Leela Bhansali on his Devdas. And it is not Luck By Chance that Zoya Akhtar’s first film did so well. And that it demystifies one of our key stereotypes today – the celebrity.

The concerns of gay cinema affect us to the point that you wonder why it is a separate genre. The label seems to exist for political rather than thematic reasons. And because it brings to the surface what has been hidden. But Brokeback Mountain was mainstream. And so was Transamerica….

These films suggest that in order for gender to be real rather than an abstract construct, it must accommodate ambiguity and play. Can’t Afia have a child by artificial insemination and can’t her son do without a known paternity? Can’t we have angry young women or must they all be tall, dark and handsome brooders like Amitabh Bachchan? And what about some more Nadias please? Can’t we have some freedom too to experiment with our sexuality and individuality? “I want to break free… ” sang Freddie Mercury. Maybe that’s what gay cinema is all about.

More Photos

2 http://www.doingbeyondgender.net/cms/en/141/?c=Film_Docu

3 http://www.wadiamovietone.com/ – see video

http://www.nextgennow.org/node/38

4 Wadia Movietone film, 1941

5 Rusi Karanjia interview in Fearless : The Hunterwali Story, Riyad Wadia

6 http://wp.gaybombay.org/reading/BOMgAY_making.htm

7 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YU1I69f4uMs

http://www.dnaindia.com/lifestyle/report_not-without-my-gay-son_1540707

http://wp.gaybombay.org/reading/Nish_Sarans_Summer.htm