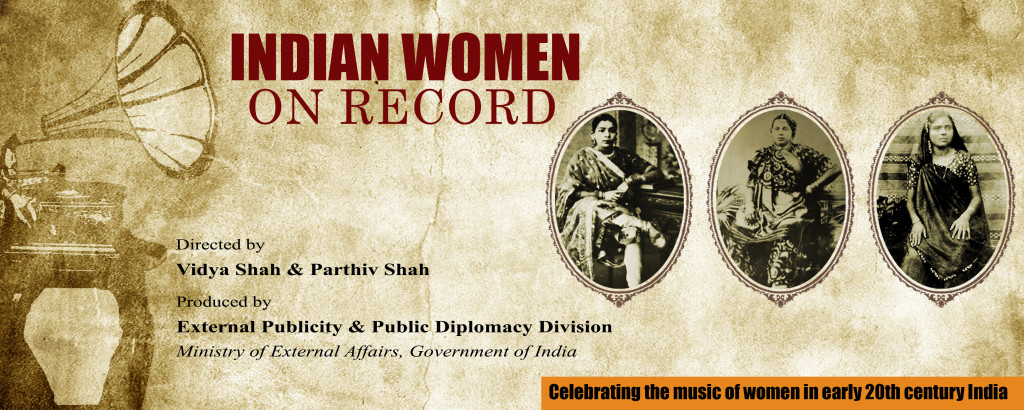

Women in the 78 RPM gramophone era made a significant contribution to Indian art, music

and literature, and were involved in theatre and film. They have had a profound influence on

subsequent performance music. Ironically, there is little available in the public memory about

the gaanewalis or songstresses; this is a legacy that has largely been preserved through

the gramophone records that first made their appearance in India in the first decade of

the 20th century. Collectors estimate that the number of records issued in India would

amount to about half a million – a large corpus of which remains unheard and inaccessible

to contemporary audiences.

Jalsa, the book is a journey through the lives and music of these singing ladies who played an important role in the making of the entertainment industry of India – an industry that is celebrated the world over today.

Even though baijis, or singing ladies, were important to the world of performance,

they were perhaps not really a part of the mainstream discussion and discourse

on music in India. While it is estimated in discographies that over 500 women

were recorded in different regional languages all over India, little is known about these

artistes. Gramophone companies, initially run by Americans and Europeans and not by

upper-caste Indians, actively recruited baijis for their early recordings.

The gramophone record revolutionized the ways in which music was heard, and

gradually also started to craft new social norms. For one, the commercial success

of the record made this avenue an attractive option for many musicians, both

performers and accompanists. Those among them who became celebrities were

clearly affluent and lived posh lifestyles, but there were also those who died in penury.

This was also the time of the nationalist movement – a struggle against foreign

rule, but also a movement with a reformist agenda. The baijis’ profession was condemned

and they were branded as ‘loose women’. Many of them then moved to the theatre and

films, given their understanding of the social stigmas faced by their community, and sensing

the opportunity encoded in cinema for a potential career change. Some – like Jaddan Bai

better known as film actress Nargis’ mother – moved from being successful and respected

performers to becoming film producers and actresses.

The voices of these women still speak to us, requiring us to imagine their historical contexts.

There are many stories of struggle, courage and marginalization as baijis made history: from

being mere entertainers to people who had generations of camp followers, creating the way

for a new language in the performing arts for women performers in India.